Facelift for an Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Patient: A Case Report

Facelift for an Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Patient

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a group of inherited connective tissue disorders caused by genetic mutations that result in faulty production of collagen. Multiple body systems can be affected, though the type of EDS depends on which collagen sub-type is involved. There are ten subtypes of EDS. Types 1 and 2 are the classical types and cause hypermobility with moderate skin involvement. These types are caused by autosomal dominant type V collagen defects. Patients with EDS have fragile skin and tissues that tear easily during operative procedures, which can complicate undermining and suturing strategies. Vessel wall fragility and problems with platelet aggregation can cause excessive bruising and higher risk of hematoma formation in the immediate postoperative period. There can also be increased problems with wound healing, stretched scars, and recurrence of redundant skin folds due to poor collagen synthesis during the proliferative phase after injury.

Facelift and necklift procedures have previously been deemed to have inappropriately high risks of complications in EDS. We present an interesting case to highlight these principles in a patient whose quality of life was severely affected by her preoperative physiognomy.

Case Report

Figure 1 - (A, E) Preoperative, (B, F) 1 day postoperative, (C, G) 1 year postoperative, and (D, H) 22 month postoperative photographs of this 55-year-old woman.

A 55-year-old woman with EDS (type 2, classical) presented in April 2013 with severe skin laxity of her face and neck, requesting rejuvenation surgery to address her premature facial and cervical ageing in order to restore her self-esteem. She had experienced extensive postoperative bleeding and bruising previously from surgical procedures undertaken on her wrist and knee joints, and had profound awareness of her condition at her initial consultation with the senior author.

Download the Case Report

At subsequent assessments, spanning over four months, it was mutually agreed that standard face and neck rejuvenation procedures were high risk in her case, but the procedure could be modified with limited tissue excision and conservative tissue handling to titrate the surgical outcomes to her realistic expectations. The patient fully consented, and the risks of significant scaring postoperatively due to her condition were clearly outlined to her. The procedure was performed in August 2013. Her preoperative photographs demonstrate excess skin in the jowls, the upper part of the neck, and the lower part of the neck, which were the patient's main concern (Figure 1).

A Modified Rhytidectomy

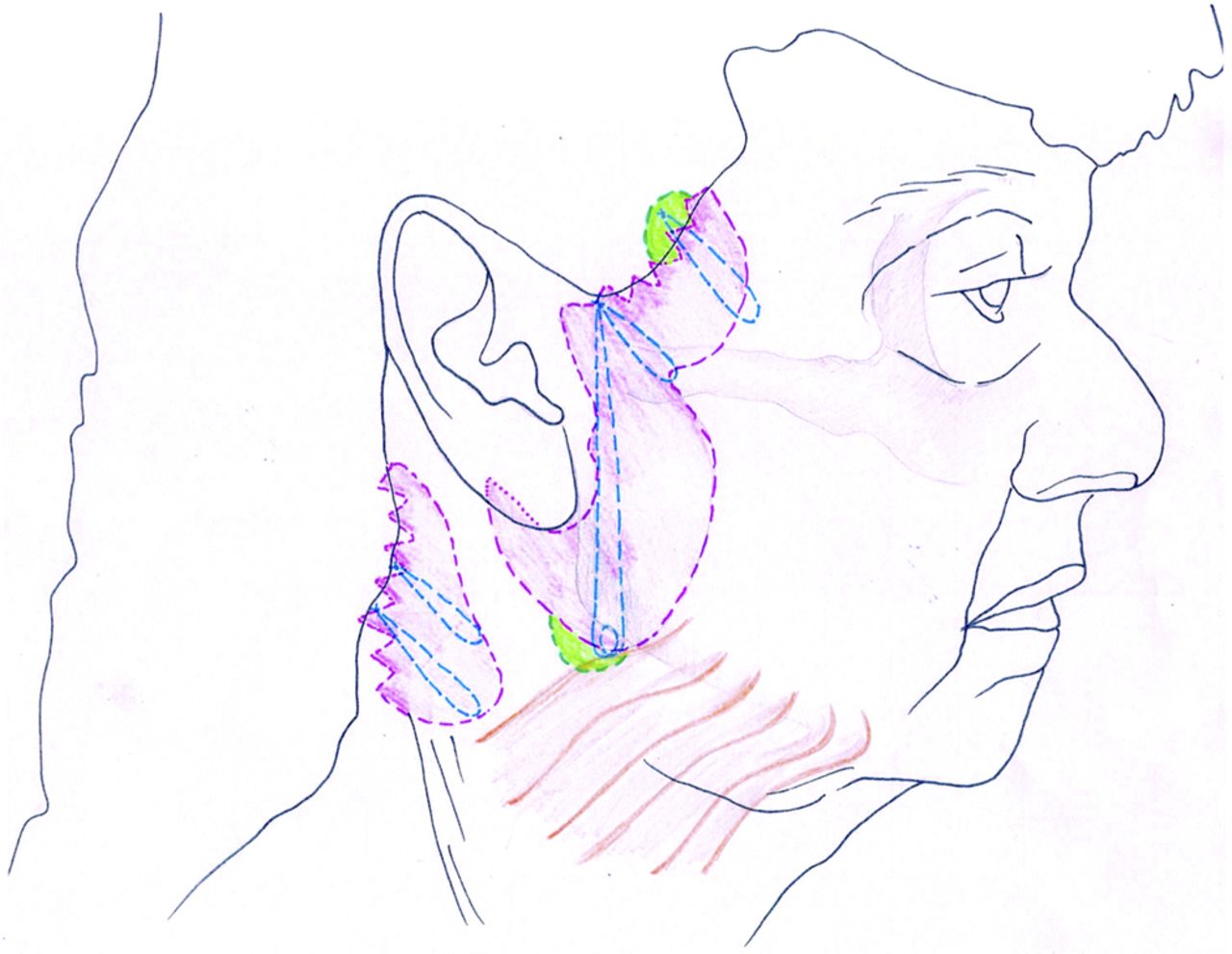

Figure 2. - This illustration highlights the main areas addressed in the posterior cervicoplasty technique. “U” suture: MACS-like SMAS plication from temporal fascia above zygomatic arch, includes posterior edge of platysma. “O” suture: dermis and subcutaneous tissue, including SMAS to temporal fascia above the zygomatic arch. Third suture: dermis and subcutaneous tissues to temporal fascia above zygomatic arch. Posterior cervicoplasty sutures skin and subcutaneous approximation sutures using 3.0 PDS. Further 3-0 PDS skin approximation sutures from the deep dermal layer to the pre-auricular epichondrium (purple shaded area, skin excision; green shaded area, two small areas skin of undermining to facilitate suture placement).

The markings were made before the operation in the sitting position. An initial temple to post-earlobe skin marking was made as for a minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) facelift. The patient's skin laxity was assessed, and a second skin marking was made on the cheek and neck (Figures 1E and 2). The patient had general anesthesia, and routine infusion of lignocaine with adrenaline was given. The shaded zone of skin and subcutaneous fat between the two lines was excised down to SMAS without undermining (Figure 3). After meticulous hemostasis, a composite lift of the facial and neck tissues below the inferior border of excision was performed along a vertical vector by using a 2/0 Ethibond “U” suture (Ethicon, LLC, Somerville, NJ).

The “U” suture was from the deep temporal fascia, above the zygomatic arch to a point below the angle of mandible. This requires 1 cm skin undermining inferiorly to take bite of the platysma (Figure 2). This “U” suture is like that of MACS facelift. Multiple bites of SMAS were taken in both directions. This suture was not cut short at this stage and the same loop of 2/0 ethibond was used to complete the middle “O” suture. This elevated the neck and created the angle between the chin and neck. This suture mainly restores the skin tightness of the upper and middle neck and improves the definition of the cervicomental angle.

Figure 3. - Intraoperative view of one of the skin excisions.

A third suture of MACS facelift type was placed before the middle “O” suture. This requires 2 cm undermining of the superior margin of the wound to expose the temporal fascia (Figure 2). The dermis and subcutaneous tissue of the inferior skin edge to the temporal fascia was secured using 2/0 ethibond. This provides elevation of the cheek soft tissues to improve the support of the lower eyelid.

The remaining loop of “U” suture was used as an “O” suture to elevate the central part of cheek and was secured to the temporal fascia. This suture improves the nasolabial fold to jowl area of the face, including elevation of the angle of the mouth, by securing the dermis and subcutaneous tissue of the distal skin flap to the temporal fascia above the zygomatic arch.

Further, a 3/0 PDS suture was used to approximate wound margins and to elevate, at the same time fixing the tissue to Lore's ligament anterior the neck and jowl, to the tragus, which is a fixed point. At this stage, both wound margins of the skin excision become almost approximated. Skin and subcutaneous tissues were sutured with absorbable sutures. This two layer suturing prevents any tension over the wound edges, with the aim of preventing scar widening.

Technique for Posterior Cervicoplasty

The skin excision was undertaken as marked (Figure 2) and 3/0 PDS sutures were employed to approximate the borders of the excision, thereby elevating the ptotic lateral and inferior neck, and improving the cervicomental angle. Double layered closure wass employed for the skin and subcutaneous tissue approximation using absorbable sutures and again, no undermining of skin flaps was performed (Figures 2 and 3).

Steri-Strips (3M, St. Paul, MN) were applied to the wound and gauze, wool, and crepe bandages were used as a head bandage for gentle compression overnight.

RESULTS

Postoperative Course

The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery. There was no bruising on the face and neck. However, she did have severe bruising at the IV cannulation line site. Figure 1 demonstrates the patient at 1 day, 1 year, and 22 months postoperatively. Note the minimal bruising on day 1 postoperatively (Figure 1B,F). At follow-up, she was noted to have uncomplicated wound healing and after more than one year, the scars had settled well. The patient was delighted with the surgical outcome and stated this in a letter to the leading surgeon involved in this case.

The long-term follow-up photographs also demonstrate that without the use of an “anchor” stitch to a fixed point, there can be direct tension on the skin edge. In patients with connective tissues this can cause scar widening.

DISCUSSION

We compare this case to another reported in 1985.3 The patient described was a 62-year-old woman with EDS. In that case a standard face and necklift was performed, but there were severe operative difficulties as routine steps could not be executed. The patient had a stormy postoperative period with severe bruising and multiple returns to theatre for evacuation of hematomas.

Guerrerosantos and Dicksheet demonstrated postoperative complications at day 3 in a female patient with EDS syndrome (the particular type of EDS was not documented). Severe ecchymosis was noted. An extensive review of the literature involving rhytidectomy within EDS patients was conducted, and only the one case reported above was found. Patients with EDS requesting rhytidectomy procedures represent a challenge to plastic surgeons which has previously been considered insurmountable.3 We have adapted standard facelift techniques to reduce invasiveness with this new technique for this high risk patient cohort. This will avoid the policy which is generally employed by plastic surgeons when confronted with a request for a rhytidectomy by patients with EDS.

We feel that whilst our patient did not have the most severe form of EDS, she did in fact have a connective tissue disease that put her at a significantly increased risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications directly effecting her rhytidectomy. Despite this, our modified technique demonstrates the success of no undermining and the possibility of cosmetic and corrective surgery for this cohort of patient, without the complications.

CONCLUSION

This limited composite facelift technique is a modified MACS procedure with no undermining. Despite this conservative approach, this technique uses deep lifting sutures of the MACS lift technique, elevating tissues along a vertical vector producing a more natural looking stable result at 1 year follow-up. This has encouraged us to offer the technique to many of our routine primary and secondary facelift patients. We now routinely perform this technique as a day case procedure under local anesthesia with sedation.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

© 2016 The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Inc. Reprints and permission: journals.permissions@oup.com

REFERENCES

1 ↵De Paepe A, Malfait F. Bleeding and bruising in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and other collagen vascular disorders. Br J Haematol. 2004;1275:491-500.CrossRefMedlineWeb of Science

1 ↵De Paepe A, Malfait F. The Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a disorder with many faces. Clin Genet. 2012;821:1-11.CrossRefMedline

1 ↵Guerrerosantos J, Dicksheet S. Cervicofacial rhytidoplasty in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: hazards on healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;751:100-103.CrossRefMedline